The recent ratio of tasting to drinking has been absurdly high. I’ve spent the last seven days in Tuscany for the Anteprime—a preview of new vintages and a retrospective of existing ones across Chianti Classico, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, and the broader Tuscan denomination, although the Brunello and San Gimignano producers don’t take part.

More on that another time, but after dozens of Sangiovese a day, broken only by the odd Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot and the very occasional Vermentino, actually drinking wine wasn’t terribly high on my list. To be honest, I ended most days gasping for the cold, fizzy neutrality of a lager—like just about every other wine taster I know—and desperate to scrub the blue-black tasting gunk off my teeth, tongue, cheeks, and lips.

After the oral hygiene and lager-drinking requirements had been met, some wine drinking was achieved. But, given the context, it made me reconsider the differences between tasting and drinking. It’s an old chestnut that these are not the same thing, and that’s true, but for me, the difference isn’t in the swallowing—it’s the mindset.

When I drink, I’m focused on pleasure and subject to inebriation, so I’m not really analysing the wine. That means my thoughts and reflections on wines I’ve drunk are less technical, detailed, and objective than when I taste—and often much more discursive and wide-ranging, touching on things well beyond wine.

When I taste, I’m much more focused. I normally think about a wine from as objective a point of view as possible, considering not only my personal feelings on what, say, Chianti Classico should taste like but also the range of flavours, approaches, and styles that producers make and wine drinkers enjoy. I approach it more technically, within a framework, and tend to only consider the wider elements after I’ve finished tasting and have time to debrief myself or analyse my notes.

Yes, wines evolve in the glass and in the bottle as you drink them—something that can’t be appreciated in a quick tasting assessment. But it’s very rare for a wine I thought was worth an 88 to suddenly find itself a 92 just because it’s had time and air. More often, my understanding of what makes it an 88 simply becomes more complete as it sits in the glass and is drunk with or without food.

Speaking of old chestnuts, there’s been a fresh round of chatter on wine scores recently (see Simon Woolf’s comment-provoking piece at The Morning Claret, which I highly recommend subscribing to). But, I have to confess, it’s a subject that annoys me. Every six months or so, there’s a piece about how wine scores are problematic and should be abolished, roughly alternating with other hand-wringing pieces about whether wine writing is valuable or relevant.

Talk about eating your cake and having it; if we followed most of these articles, we’d neither score nor write about wine, and yet writing about writing and writing about scoring prove remarkably fertile ground.

The key confusion is around the idea that because it’s a number, it must be objective. That’s just a mistake. An 89 isn’t inherently more objective than “excellent” in this context, and once you realise that every score is a subjective score, the whole thesis basically falls apart. It’s almost entirely based on the straw man argument that all 87s are equal across all reviewers and publications—which is like saying every instance of the word “redcurrant” is used in exactly the same way by all writers, since it refers to a pretty definite and defined thing.

Two teachers might mark an exam differently (which is why examination panels exist to review and standardise results), two critics might score a theatre show out of five stars differently, and two wine critics might award an 89 and a 93 to the same wine. So what? No one is pretending they’re establishing an indisputable fact about a wine—they’re giving their informed opinion in words and numbers. Do we think that when gymnasts are given scores at the Olympics by a panel of judges, we are establishing immutable facts of science and nature around their performances? Of course not.

There’s particular resistance to scores among natural wine fans, largely because it’s considered reductive and simplistic in the face of wine’s complexities. But I don’t think scores demean the beauty of wine, since most of what I taste is not beautiful, and I don’t think they over-simplify wine either.

In fact, I think people who write about wine tend to over-complicate it as result of their passion—which is perhaps why the cold clarity of a score upsets them, subliminally reminding them that most wines are either poor, good, very nice, or amazing, and that they need to decide for themselves which it is.

Broadly, that’s all that scores do. Each publication has its own rubric, which you need to pay attention to, but generally anything below 85 is borderline faulty or poor, anything 85–89 is good to very good, 90–94 is excellent/outstanding, and 95+ is amazing/classic/life-changing. These are bands—which is why bronze, silver, gold, and platinum medals map onto them so neatly. It therefore makes sense that we see spikes in the numbers (as demonstrated in Simon’s piece) at the beginning and end of the bands.

The challenge with scores is to find a way to deploy them intelligently, and with context, like everything else in life. A lot of fellow professionals pretend to ignore scores, but I look at them all the time. When I read a fellow writer’s tasting note, I look at the score first, then I read the note (which sometimes explicitly mentions and justifies the score), and then I make a judgement—based on that taster—on how I might feel about the wine.

It’s pretty straightforward. Most wine drinkers will spend approximately three seconds on a wine before deciding if they like it, and will probably work on an even more limited scale of nice and not nice, or words to that effect. The anxiety around scores reflects more on the scorer than the scoring.

Let me know what you think below, and in the meantime, let’s drink and not score some wine…

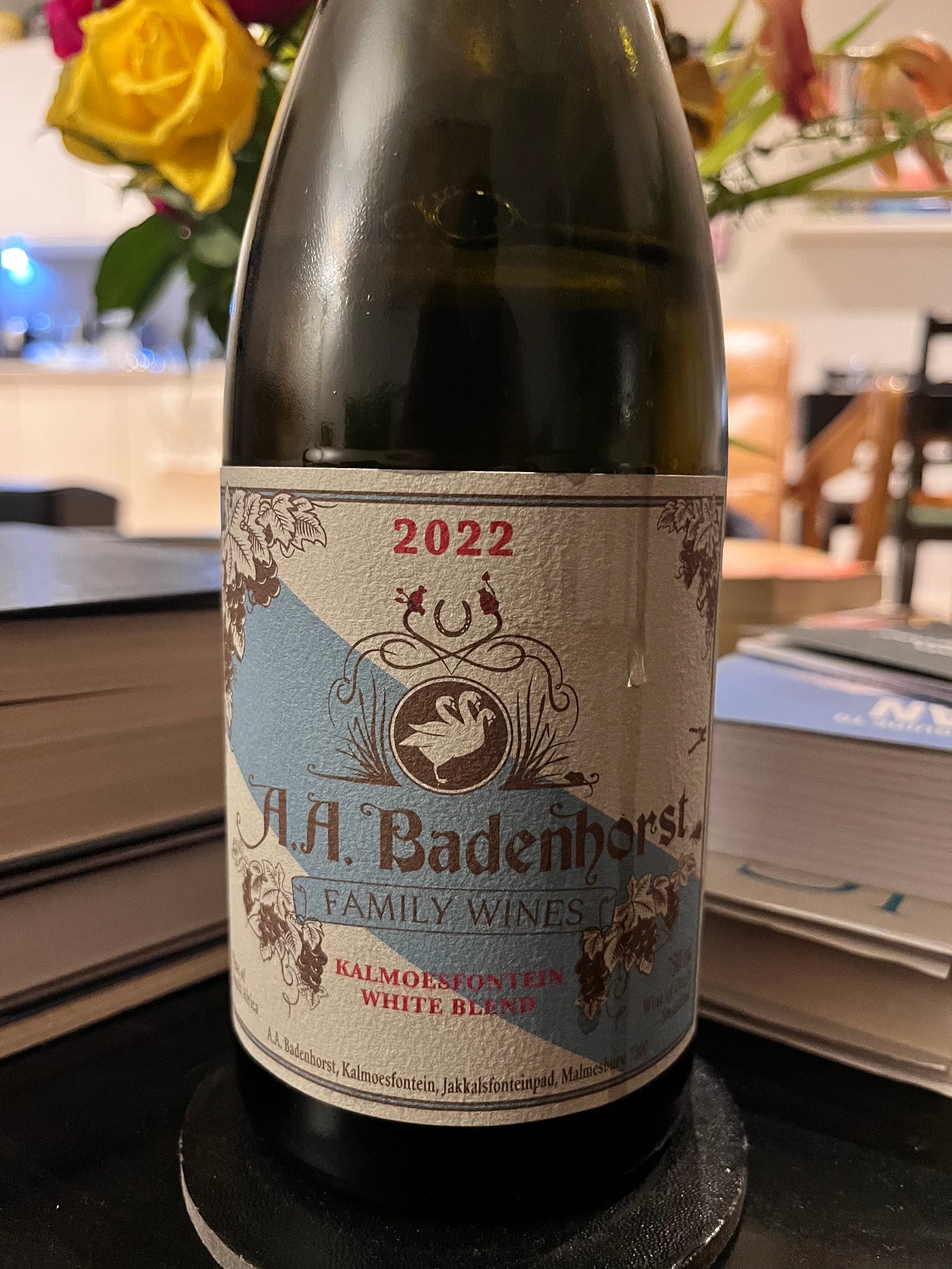

A.A. Badenhorst Kalmoesfontein 2022, Swartland, South Africa

This was sent as a sample for a piece I was writing for Decanter, but it didn’t quite make the recommendations list. These Cape white blends are such extraordinary and unique wines. They’re also a bit difficult. Often set up as white Burgundy alternatives, in reality they’re more like white Rhône alternatives—and that’s a tricky category in itself. To provide a little bit of a foil to my polemic about scores in the intro, this would actually be a tough wine to score (but not impossible) as it’s quite hard to read and rather discreet, if very delicious. It was intense, palate-coating, and fairly low in acidity, with lots of quince, banana, and yellow apple, finishing with a waxy texture. Not for everyone, I imagine, but impressive and age-worthy. I’d like to come back to this in five years.

£35, Swig

Piero Busso Mondino 2021, Barbaresco, Italy

I absolutely love the Busso wines, and buy and drink them regularly. I think he makes better wines than some of the very famous (and very expensive) producers in Barolo. I ordered this in a smart restaurant in Florence and was impressed with its concentration and intensity. It’s very 2021—a vintage about which there’s a lot of excitement. If you have it, I’d wait; if you don’t, I’d buy it and keep it. It’s a great wine but needs a few more years to shed some tannin and integrate its structural buttresses. Buy the rest of his wines too, while you’re at it. San Stunet is a consistent favourite of mine, vintage after vintage.

£69.75, Sip Wines

Istine Vigna Casanova dell’Aia 2018, Chianti Classico, Italy

If there’s one producer in Chianti Classico who really proves that Radda is the most elegant and charming of the villages, it’s Angela Fronti at Istine. I really don’t know how she does it, but she brings an extra level of clarity and brilliance to her wines that no one else quite manages. I didn’t buy this one — it was poured as part of a producers’ dinner. This was an absolutely stunning wine from the family’s first vineyard, situated in Radda at 500m above sea level. It is a brilliant success, in the difficult 2018 vintage—high-wire, elegant, and as pretty as you could wish for, with notes of fresh pomegranate, citrussy acidity and super-fine tannins. And to think that Angela was once told that her wines were too high-acid and should be blended with Merlot…

c.£37 via AB Vintners. Note this is bottled as a Gran Selezione from 2021 vintage.

Frescobaldi Vigna Montesodi Riserva Terraelectae 2019, Chianti Rufina, Italy

I don’t normally generalise about vintages, but the 2019s in Tuscany often have a plush, smooth texture that’s really distinctive and unusual for Sangiovese. There’s just something more velvetty and smooth about this Riserva from Castello Nipozzano compared to other vintages. This was a perfect example of a wine that’s normally pretty aerial and red fruited that has been given a bass line and a velvet dinner jacket by the year. Definitely ready to drink, and the 2021, which I tasted twice, was looking very fine too.

£41.95 for the 2021 at VINVM, and other merchants via Wine-Searcher.com